By Barry Darby and Helen Forsey

Introduction:

This is an adaptation of the presentation given by Barry Darby and Helen Forsey, of Changing Course, to the 4th World Small-Scale Fisheries Congress (North America), St. John’s, NL, June 20, 2022. It summarizes the central ideas in their policy paper, “Changing Course – A New Direction for Canadian Fisheries.”

Barry Darby grew up on a fishing room on Great Burin Island. He fished with his father for several years before becoming a science instructor at the College of the North Atlantic. In the 1990s he was Co-ordinator of the Fisheries Adjustment Program at the College. One way and another, he’s been working on fishery policy ever since. Helen Forsey is a writer, translator and activist, with a background in agriculture, international cooperation and policy analysis. They have been working together on fishery issues for the past four years.

1. Changing Course:

Research and Advocacy on Fishery Policy

In Changing Course, we research fishery policy and advocate change. Government policies underlie and regulate most of the activities that fish harvesters and processors engage in. That is what fishery “governance” refers to, and we need to get it right.

So, what are the existing policies, and why are they not ensuring a sustainable fishery? In this session we propose a paradigm shift in policy direction that will radically change the framework that now exists to one that will increase benefits for all concerned. At the end you will have a new window for looking at fishery management, and an alternative framework for implementing sustainable fishery policies.

2. Sustainability Stool

What should be the goal of fishery policy? Most would agree it’s sustainability.

But sustainability isn’t just a single simple thing. Look at it as a stool with three legs – environmental sustainability, social sustainability, and economic sustainability.

The stool needs all three legs in order to stand; if any leg is missing or weak, too short or too long, the whole sustainability stool will overbalance and collapse.

Likewise, good fishery policy rests on all three legs. The policies need to optimize the ecological, social and economic benefits for the present and future, and for all involved.

3.Thomas Hardy quote:

“If way to the Better there be,

it exacts a full look at the Worst.”

Here’s one of our favourite quotes: “If way to the Better there be, it exacts a full look at the Worst.” So wrote Thomas Hardy back a hundred and some years ago, perhaps never realizing it would apply so perfectly to fishery management. But it does.

4. A Look at the Worst

We’ve been Getting It Wrong

Evidence:

- 30 years of cod moratorium

- decimated coastal communities

- decline of 3Ps cod

- fishing down the food web

Since we’re looking for a “way to the Better” for managing our fisheries – first we have to look at the Worst. The federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans bases their management system on quotas. They call it a “Precautionary Approach Framework,” or “PA Framework.” But it’s not working. Their current approach is just not sustainable.

Look at the evidence: the northern cod Moratorium – 30 years now and counting; the drastic decline of cod in 3Ps in the past two decades; the continuing struggle of harvesters just to make a living on the water; the ongoing decimation of coastal communities, the way we’re fishing further and further down the food web, as Daniel Pauly warns. DFO’s current policy framework is not protecting the ecosystem, and it is not maximizing benefits for harvesters or coastal communities either.

We’ve been “Getting It Wrong.”

5. A Way to the Better

A Paradigm Shift:

- Incentivize small-scale fisheries

- Manage by effort (inputs)

- Reduce fishing pressure

What we are proposing is an alternative framework – a new way of looking at the problem: a paradigm shift – in thinking, in policy and then in practice.

In Changing Course we have a quote: “Anomalies in a paradigm are evidence of the need for a paradigm shift.” And as we’ve noted, there’s no shortage of anomalies in the current fishery management approach.

We propose a better way that’s in keeping with the focus of this small-scale fishery Congress, and in particular with “Getting Governance Right.” What is that better way?

- First – Our overall policy direction should incentivize small scale fisheries rather than encouraging and subsidizing large, corporate, industrialized fishing, as is done at present.

- Second – We need to change our policies so that fish harvesting is managed almost exclusively by input controls or effort, not by quota. We explain in detail later.

- Third – We need to reduce the pressure on the stocks. A major review, “Rebuilding Marine Life,” was published in Nature in 2020. It recommends, among many other things, a reduction in “fishing pressure” on the stocks. So by controlling fishing effort, we reduce that pressure, and monitor the results to make sure that it’s happening.

This is the shift we must make: from output controls to input controls – from quotas to effort.

6. Managing Nature?

Humans don’t control Nature –

we’re part of the ecosystem.

The “Honourable Harvest” –

respect and reciprocity.

Ecosystem approach needed,

not “managing” single stocks.

We’re talking about a paradigm shift in management. But before detailing the specifics of the solution we propose, let’s step back and set the context at a more general level. There are three inter-related aspects to this:

- First, we humans are part of the natural world, not separate from it. As Climate Change is showing us, we are not in charge. We need to recognize that in fishery management, it’s not the fish that we’re managing, it’s the fishery – that is, the human activity.

- Secondly, Indigenous traditions are grounded in exactly that reality: we are all part of the ecosystem. Indigenous languages and cultures reflect this at every level. As Potawatomi scientist and poet Robin Wall Kimmerer explains, the Indigenous concept of the “Honourable Harvest” bases its unspoken rules on respect and reciprocity with “All Our Relations.” Take only that which is given. Harvest in ways that minimize harm. Never take more than half. Never waste. We are slowly starting to pay attention to those profound understandings, but we’re still just taking baby steps.

- Finally, in fisheries circles internationally, there is now considerable agreement that fishery management should look at the whole ecosystem and work with it, instead of trying to manage single species in separate theoretical silos. Obviously the ocean is not divided into silos, and that fragmented approach is out of touch with reality. DFO is planning to eventually move towards an ecosystem approach, but they’re still managing the fishery species-by-species, stock by stock, quota by quota.

7. Our Framework

Principles:

- Healthy, sustainable ecosystem

- Harvesters have “use rights” to the ocean commons

- Optimize net economic and social benefits

- Management simple and effective

In our paper, Changing Course, we set out four principles underlying our proposal. Here is the basis of our framework:

- The ocean’s ecosystems must be kept healthy; all harvesting must be done in sustainable ways;

- The ocean is a commons, and, as the FAO recommends, harvesters have “use rights” to harvest that commons sustainably;

- The management system must provide optimum net economic returns to harvesters and coastal communities;

- Implementation and management must be as simple and effective as possible.

8. Humans as Predators

- Super-predators?

- Preserving prey

- Selective harvesting

Dr. Chris Darimont from the University of Victoria writes about humans as “Super-Predators“ because we are the only apex predator that has wiped out or brought to the edge of extinction any number of prey species. Darimont’s research shows that wild (non-human) predators preserve stocks of their prey by taking mainly the young. We should mimic those non-human predators if we want to harvest sustainably.

We can do this by harvesting selectively, mainly through our choice of gear. By using selective harvesting we can actually increase the size of the harvest while simultaneously improving the sustainability of the stock. A win-win situation.

The next section helps to illustrate this.

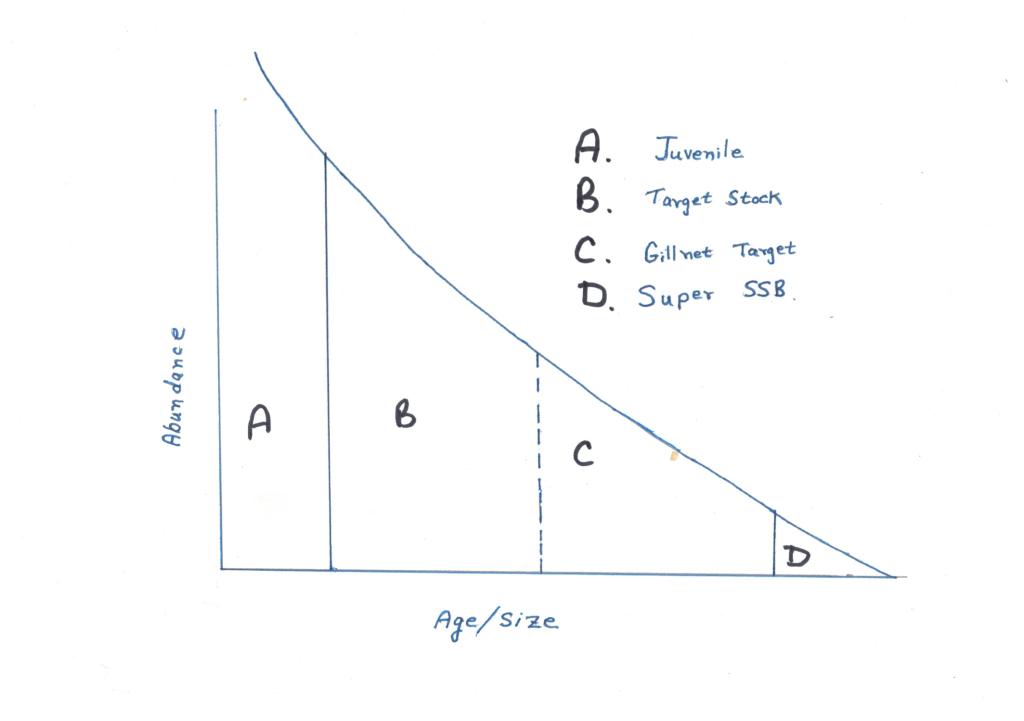

9. Fish Stock Graph

This is a typical curve showing stock abundance declining over time. Areas B, C and D represent the harvestable biomass. Note that the greatest abundance is in Area B. The dotted line between B and C shows the smallest size we catch with gillnets.

If we use selective fishing to target area B, we mimic wild predators. This way we maximize the catch, leave the veryyoung and the old, and maintain sustainability.

Later we’ll have more to say about selective fishing, and we’ll talk about the fish in Area D – the big mother fish that we might call the “super-spawning stock biomass.”

10. The Lobster Model

- Has no quota!

- Puts science into practice

- Mimics non-human predators

- Draws simple rules from complex science

When I attended a talk by Professor Darimont on humans as super predators some years ago, I had an “Ah-Hah” moment! I said to myself, “That’s how we fish lobster!!! We mimic wild predators. ‘”

The way we fish lobster in Newfoundland and Labrador puts this human predator science into practice.

A key element of this “lobster model” is that there is no quota. Instead, the rules specify the type of gear, the number of traps, the size of the openings, etc. This regulates the size of the lobsters caught and thus protects the young juveniles. To protect spawning females, harvesters must return egg-bearing and “V-notched” animals to the ocean. This ensures that the annual catch consists almost entirely of animals from the middle area of the stock graph. There’s a defined season, giving the stock and the ecosystem a chance to adapt to the large removal of lobster biomass. Most of these measures mimic the behaviour of wild predators, and we end up with large harvests when lobster are plentiful, and smaller harvests if they are scarce.

This harvest management system was put in place after a three year moratorium in the 1920s. For more than 90 years since then, we have had a highly successful lobster fishery in our province. It has proven to be both sustainable and profitable. Again, there are no quotas; harvesting is managed by regulating the fishing effort involved. Our proposed alternative system – Input-Based Management (IBM) – is modeled in large part on this.

In addressing the complexities of fisheries biology, the actual harvest regulations for an input-based system can be remarkably simple. In 1927, when the Government of Newfoundland introduced this management system for lobster, it issued a booklet detailing, in four pages, the complete harvesting and processing rules for the species. Current rules use a lot more words, but the practices themselves have changed little in over ninety years. And under this input-based system, lobster remains one of our most successful fisheries, economically and ecologically.

11. Fishery Manager’s Toolbox

So given all this, how do we go about managing our fisheries? Think of it as DFO’s fishery managers having a toolbox with a set of tools. Fisheries management involves choosing which tools to use and how to best combine them.

12. Input and Output Controls

Inputs

– Who

– How

– When

– Where

Outputs

– How much

The five main tools in the fishery manager’s toolbox can be shown as five questions – the Who, How, When, Where and How Much of harvesting. They can be divided into two groupings, representing the two main management approaches outlined in the FAO’s Fishery Manager’s Guidebook – input controls and output controls.

Input control systems regulate fishing effort: the Who, How, When and Where of harvesting. That input-based management system is the alternative framework we propose – managing harvests by regulating fishing effort.

Output control systems try to control the output: “How Much” gets harvested. Output controls rely heavily on calculating Total Allowable Catches and allocating quotas. This is DFO’s current management system, which they refer to as their “PA Framework”, and which we call “Quota-Based Management.”

13. What We Propose

Input-based Management

Uses 4 tools together:

- Who can fish (certification)

- How we fish (gear – size and number, methods)

- When we fish (seasons)

- Where we fish (zones)

The “Input-Based Management” system we advocate regulates fishing effort, using all of the first four tools together – the “Who,” “How,” “When,” and “Where” of harvesting.

The first tool is: “Who can fish.” Only certified harvesters who have registered their home port would be able to fish commercially.

The second tool, “How,” regulates the kind, size, and amount of fishing gear that can be used. Some examples:

- Hook-and-line harvesters could use 1200 baited hooks daily.

- On a trawler, a given number of harvesters could use one otter trawl of a certain size.

- Other size limits could be employed, the length of a net or line, the volume of a trap or pot, the opening of the front of an otter trawl, etc.

The third and fourth tools are seasons and zones – the “When” and “Where” of harvest management. Seasons would be set for specific zones, guided by a massive increase in Marine Spatial Planning, with many more zones and sub-zones than currently exist.

Here is an important takeaway: These four “input” questions all have answers that can be easily and accurately identified, measured, complied with and enforced. They are “known knowns,” a necessity for effective management. In contrast, as we shall see shortly, the current quota-based system is full of unknowns and uncertainties.

14. Positive Inefficiencies:

Ensuring next year’s harvest

A major aspect of good management involves the second tool – the “How” of fishing. With modern discoveries and technologies, humans now have the ability to fish out most species in a few years or even less. We no longer need to “improve” the efficiency of a gear. If we want to ensure sustainability of a species we need to leave animals in the water for the coming years. So fishery policy needs to ensure a degree of in-efficiency in our gear, in order to allow some fish to escape capture and maintain the stock and the ecosystem.

Some gear has a natural degree of positive inefficiency. For example:

- baited hooks only remain effective for a few hours;

- traps catch mainly small fish;

- small seines can not encircle a whole school.

Other types of gear need to be adapted to a lesser degree of efficiency, usually by specifying mesh size or limiting overall length and depth so as to allow certain sizes and species of fish to avoid capture. Again, all those aspects of gear can be accurately measured, specified and managed.

What an idea! Use more “in-efficient” gear and we increase sustainability! But it works.

15. Gear Sustainability Index

This section shows how gear can be ranked according to sustainability (The specifics might be different for different species and areas). It reflects what we said earlier about how managing the type and amount of gear can help us fish selectively.

On this graphic, the gears lowest down – handlines, pots and traps, and long lines in particular – have been shown to be less severe and therefore more sustainable fishing methods. They harvest selectively, catching disproportionally more of the abundant smaller fish. In contrast, those gears highest up on the index are less sustainable. For example, bottom gillnets actually target the larger fish, especially the mother fish, and bottom trawls are even worse, catching everything indiscriminately.

In our proposed input-based management system, regulations will actively favour the more sustainable gear.

16. The Current System – Quota-based Management

Uses the 5th tool – “How Much”

- Surveys, projections (each stock)

- Computer models, reference points

- Total Allowable Catches (TACs)

- Quota allocations

Contrast the input-based management (IBM) system outlined in the preceding slides with the way DFO now manages our fisheries. This current quota-based system uses mainly the fifth tool – “How Much.” It attempts to determine How Much fish we should harvest from a given stock in a given year.

Here’s how it’s done: DFO managers use survey data to estimate the biomass of a given stock. These data, which have high margins of error and uncertainty, are then fed into computers, along with reference points calculated from historical data, which also involve multiple major variables, uncertainties and unknowns. The computers then model future scenarios as best they can, plotting projected biomass numbers and removals on a graph. The point on the graph where two lines intersect leads to the decision on the Total Allowable Catch – the fundamental basis for DFO’s harvest management planning.

DFO’s management framework does use some input tools as well, with some regulations for gear, licensing, seasons and zones. But input considerations are overridden by the top priority – setting TACs and quotas. In their output control system, those TACs and quotas are the final arbiter to determine harvest policies.

As we’ll explain next, this Quota-based system is badly flawed.

17. TACs: An Impossible Task

Example (2J3KL cod):

Estimated SSB – 300kt to 500kt

Potential growth – 10% to 30%

TAC /Yield = 30kt to 150kt

One of the fundamental flaws in the current system is that TACs are impossible to calculate. This slide illustrates that fact. It shows the estimated spawning stock biomass for 2J3KL cod, probably the most highly researched of all Canada’s fish stocks. DFO’s recent stock assessments are between 300 and 500 kilotonnes – in other words, there’s a margin of error of plus or minus 25%. Estimates of other stocks are even more uncertain. In addition, historically and today, humans have sustainably harvested at least 10 to 30% of this and similar cod stocks.

As the slide shows, calculating the TAC based on those variables results in a huge range of answers. But to set a TAC, you have to have a specific number. So there’s a huge risk of getting it wrong. To have a sustainable fishery, we need to get it right.

18. (Over) fishing

Overfishing = fishing beyond a prescribed limit

So, what do we need to limit?

- the amount of fish caught? or

- the pressure (effort) exerted?

In fish harvesting policy, getting right means, among other things, preventing overfishing. We all agree that overfishing is “a fishery that removes more fish than biological production can replace.”

For us, overfishing is fishing too much, not catching too much! For example, 50 huge industrial trawlers working over same area continually for a year with otter trawls is overfishing, whether they catch a lot or very little.

Operationally, harvest managers must set limits that will prevent overfishing. So, should we place limits on the amount of fish to be caught, or on the effort exerted? Our view is that we should place the limits mainly on the effort. With input-based management, unlike a quota system, we can accurately establish, quantify, adhere to, monitor and enforce all the elements involved in harvesting our oceans, and thus proactively prevent overfishing.

19. … and Underfishing – Foregone Harvests

Unnecessarily low harvests result in

– Economic losses

– Ecological harm

Solution: Manage inputs (effort)

With Quota-based management there are two parallel problems – overfishing on the one hand, and what we’ll call “under-fishing” on the other.

Since TACs and quotas are based on wildly uncertain assumptions and calculations, they often limit us to much smaller harvests than what we could safely catch sustainably. This type of unnecessary loss is referred to as “foregone harvests.”

Foregone harvests mean major economic losses for harvesters, processors and communities. Catching too little can also be bad for the fish stock itself. If there are more hungry fish than the available food supply can support, those fish will be in poor condition and there will be starvation. In such cases, leaving too many fish in the water is ecologically counter-productive.

Solution? Again, we should fish selectively, managing the fishing effort so as to catch a larger proportion of the hungry predator fish and leave more prey for the remaining ones to eat. Those remaining predator fish will then be in better condition and can grow, reproduce and more effectively replenish the stock.

Input-based management (IBM) prevents both over-fishing and under-fishing. Its built-in feedback loops and selective harvesting methods enable us to catch more fish when fish are plentiful, with appropriately lower harvests when fish are scarce. That way we can actually fish less, and catch more.

20. Is the current system Precautionary?

“If the highest aim of a captain were to preserve his ship,

he would keep it in port forever.”

~ Thomas Aquinas

With the clear decline of major marine species over the past seven decades, many respected fisheries scientists and advocates like Daniel Pauly have called for a precautionary approach. DFO’s quota-based management system is an attempt to implement precaution, but the evidence shows it doesn’t work out that way in practice.

More than 700 years ago, Saint Thomas Aquinas wrote: “If the highest aim of a captain were to preserve his ship, he would keep it in port forever.”

Similarly, if people are so fearful of damaging the stocks that they essentially stop fishing, they don’t understand our human role as apex predators in the ecosystem. We fill that role by fishing sustainably. The proof is clear in our small-scale fisheries like lobster, not to mention 450 years of sustainable cod fishery here in Newfoundland and Labrador.

The solution is NOT the often-stated command to “keep removals as low as possible” – it’s to reduce fishing pressure to where the feedback from the harvesting itself shows we’re doing it sustainably. That is what our proposed input-based management framework does.

21. BOFFFs – Big, Old, Fat, Fecund Females

Another problem with Quota-based Management is that it uses biomass estimates as the basis for harvest policy and planning. Those biomass figures measure (or rather, estimate) the total weight of fish in a given stock. But that ignores some key factors of sustainability.

For example, there’s the phenomenon of “reproductive hyperallometry.” That refers to the fact that Big, Old, Fat, Fecund Female fish – “BOFFFs” – produce more eggs and more surviving larvae than the equivalent weight of smaller fish – perhaps as much as an order of magnitude more.

But TACs are defined in terms of biomass – a kilo of fish is a kilo of fish, regardless of age, fecundity, or the condition of the fish. So that multi-dimensional complexity isn’t adequately taken into account in the quota-based system.

As Dustin Marshall and his co-authors put it in a recent paper:

“Failing to consider reproductive hyperallometry overestimates the efficacy of traditional fisheries management, and underestimates the benefits of approaches that create reservoirs of larger individuals.”

Our proposed input-based management framework embodies precisely such a beneficial approach.

22. Managing by Quota: Problems

- Environmental

- Economic

- Social

Let’s take a final look at the problems with the current quota-based policy framework. We all want our oceans to be sustainable – economically, socially and environmentally. A good management system should accomplish this. But basing fisheries management on quotas, as we currently do, actually works against sustainability. How?

Quota-based management tacitly allows all fishing methods and gears. As long as you catch your quota, you can mostly use whatever gear you want, with the main limit being the number of tonnes of fish you get. This means most harvesters will use gear that catches as much as possible as quickly as possible – which is also the gear that is least sustainable. And in our capitalist, market-driven economy, the ones with capital go big – larger boats, bigger trawls, etc. Moreover, those large-scale gear types are often incompatible with the slower, more economical and less destructive gear. So small-scale fishers using hooks, pots or traps are effectively barred from the ocean or only have limited access.

In practice, then, the quota system favours large-scale industrial fisheries. This favouritism is directly tied to DFO’s policies and regulations, which need to be changed.

We don’t have time here to go into a detailed list of negatives associated with DFO’s quota-based PA framework, but here are some:

High carbon emissions, Biodiversity loss, Habitat destruction, Plastic pollution, Low-quality products, Waste of protein, Exploitation of labour, Outmigration, Privatizing the ocean commons, Flight of wealth from coastal communities … The list goes on.

These problems can be resolved or significantly reduced by small-scale fisheries managed by input controls. And in Changing Course, we’re about solutions.

23. Managing by Effort – 1: Ecosystem benefits

- Effective feedback loops

- Responds to variable conditions

- Less environmental damage

- Lower carbon footprint

Now let’s look at the benefits of the solution we’re proposing. Input-based management works with Nature instead of making futile attempts to control it. Our system contains feedback loops that lead to a largely self-adjusting harvest, reducing fishing pressures on fish stocks and other marine life.

Basing management on inputs enables us to identify and respond to ever-changing ocean realities like food supply, natural predation, water temperature, disease and migration, all of which influence the sustainability of our harvesting.

With the use of more sustainable harvesting gear and methods, there will be much less damage to habitat and to the marine food chain, enhancing marine biodiversity. Our approach will also reduce bycatch, carbon emissions, and plastic pollution.

24. Managing by Effort – 2: Economic and social benefits

- More fish and larger harvests

- Better net returns

- Stronger local economies

- Reviving coastal communities

As input-based management becomes established, the ecological benefits will translate into economic and social benefits to coastal communities and to the economy and society as a whole.

Thanks to the more sustainable fishing practices under this approach, fish will become more plentiful, enabling larger harvests, benefitting both harvesting and processing sectors.

Higher quality products and better prices, combined with lower expenses, will increase harvest efficiency, and result in greater net returns.

The shift in policy will result in less bycatch, reducing the corresponding waste and economic losses. With the problem of “foregone harvests” resolved, economic activity will increase at both the local level and more broadly.

As people realize the benefits accruing from input-based management, harvesters will increasingly opt for smaller boats and “slow fishing” practices. This will reduce the overcapitalization of the fleet and make it easier for younger people to get into harvesting. The increased economic activity in coastal communities will strengthen local economies and help coastal communities and our Newfoundland and Labrador culture survive and thrive.

25. Getting It Right: Priority Actions

- Implement policy shift to Input-Based Management

- Make maximizing net economic benefits a formal management policy goal

So what actions do we need to take to get it right?

First, DFO must immediately begin the shift to Input-Based Management. Implementing this major change will be complex, and will take some time. But it can be started immediately, and the transition process must be structured so that as issues arise, they will be addressed.

Secondly, the government must formally prioritize the goal of maximizing net economic benefits for harvesters and coastal communities as a basic element of fisheries policy. If the fishery does not result in optimum benefits for harvesters and their communities, we are mismanaging the resource.

All three legs of the sustainability stool are essential. Small-scale fisheries, managed by effort, will strengthen all three.

2021 to 2030 is the UN’s “Ocean Decade.” There’s no better time than now to make this vitally important “change of course.”

26. Getting It Right: Other Needed Actions

- All harvesters certified

- All dead by-catch landed

- Massively increased data collection

- Harvester-processor independence

- Local involvement in decision-making

Here, briefly, are some other important elements of our approach that must be part of the policy shift we are advocating.

- All commercial harvesters should be certified. The Red Seal program for other trades could be a model.

- All dead bycatch should be landed and recorded. DFO’s current bycatch policies require or encourage the unrecorded dumping of valuable protein. Iceland’s policies and practices on bycatch address this issue.

- Collection, analysis and use of relevant data must be massively improved and expanded, as a basis for more and better research and regulation. DFO is way behind the rest of the economy in this area.

- The separation between the harvesting and the processing sectors must be clear, legislated and well-enforced. We need regulated competition at the wharf’s edge, and can look to Iceland and Norway for examples.

- Harvesters and fishing communities must be involved in decision-making on fishery policies at all levels. Policies and regulations should be designed to enable harvesters and their communities to make as many of their own decisions as possible.

27. Two Rival Frameworks

Quota-based Input-based

Let’s Get It Right!

So there you have it – a sketch of two competing frameworks – the quota system that DFO calls its “PA Framework”, and our proposal for input-based fishery management that regulates fishing effort.

Although we’ve only just scratched the surface in this presentation, our intent is to advocate a paradigm shift in fishery governance that will lead us on a sustainable course into the future.

28. Questions for Discussion

- Which policy framework do you think is better – DFO’s current “PA Framework” or the Input-based framework we’re proposing? Why?

- What problems do you see with shifting to an input-based system? How could they be resolved?